Claudia Hitaj

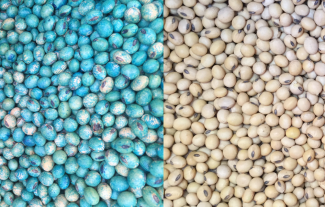

(left) treated and (right) untreated soybean seeds

Collecting accurate data on pesticide use is important, because it helps farmers, researchers, and regulators increase agricultural production and also protect the environment from the adverse effects of pesticides. While in most countries we have reliable data on pesticides that are sprayed onto fields, we do not know a lot about the pesticides that are applied as seed coatings. And if farmers do not know what pesticides are on their seed, there is a potential for pesticide overuse.

The use of pesticide-treated seeds has increased rapidly over the past decades, and the large majority of corn, wheat, soybean, and cotton fields are now planted with treated seeds. In many countries, the lack of information on the use of pesticidal seed treatments means that a significant portion of pesticide use is currently not captured in existing pesticide-use datasets, such as Eurostat’s data on pesticide sales or USDA’s data on agricultural chemical use. This is particularly true for active ingredients that are applied mainly as seed treatments.

I explored this topic with a team of researchers in an article recently published in BioScience entitled “Sowing Uncertainty: What We Do and Don’t Know about the Planting of Pesticide-Treated Seed.” We wanted to assess why existing pesticide-use datasets miss this important piece of the puzzle. Our hypothesis: survey questions were designed before the use of seed treatments became commonplace, and farmers often know more about the pesticides they apply to their fields than they do about the pesticides contained in the treated seeds they purchase.

Pesticide seed treatment is underreported

We analysed farmer surveys conducted by the US Department of Agriculture, in which we found that in the United States only 84 percent of cotton growers, 65 percent of corn growers, 62 percent of soybean growers, 57 percent of winter wheat growers, and 43 percent of spring wheat growers provided the name of the seed treatment product used on their crops. In contrast, farmers were knowledgeable about the pesticides applied directly to crops in the field, since about 98 percent of farmers provided the names of the pesticide products they used.

Lack of reporting of the pesticides applied directly to seeds is not limited to farmers in the United States. In the United Kingdom (UK), Fera is commissioned by the government to conduct one of the most in-depth surveys on pesticide usage, including seed treatments, providing data by active ingredient for 13 arable crops. In the UK, seed treatments were used on 96% of wheat acres and 89% of spring barley acres in 2018, but farmers did not specify the seed treatment product on 12% and 22% of those acres, respectively. Not specifying the particular seed treatment product may not mean that farmers are unaware, as farmers may not store the seed treatment information in the same place as foliar applications and it may thus not be as readily available when answering a survey.

What are possible reasons for the underreporting of pesticidal seed coatings?

On both sides of the Atlantic, there are several possible reasons for the reduced response rate for survey questions on seed treatments. Whichever the case, lack of “ready” knowledge on the product that was applied is not surprising given that farmers often do not treat the seeds themselves but purchase pre-treated seeds from suppliers. Farmers are thus less involved in deciding the combination of active ingredients contained in the treatment than they are about deciding which pesticides to apply directly to their fields.

Lack of data on pesticides applied as seed treatments is also the result of questions on seed treatments not being included in surveys of pesticide use by government agencies. For example, Eurostat provides data on the quantity of pesticides sold in EU member countries, but separate information on seed treatments is not included. Similarly, the federal government of Germany collects data on the pesticides sold into the domestic and export markets and the active ingredients they contain, but pesticides applied as seed treatments are not reported. While the government of France collects data on the share of acres planted with treated seeds by crop (such as more than 92 percent of wheat, barley, corn, sugar beet, and linseed acres in 2017), information on the active ingredients contained in the seed treatments is not collected. The UK pesticide usage surveys mentioned above form the notable exception.

What is the situation in Luxembourg?

Since the 2012-13 growing season, the government of Luxembourg publishes annual data on pesticide use by active ingredient for 10 crops, though seed treatments are not listed separately and not included in the case of imported treated seed.

However, for the first time in 2019 and as part of its National Action Plan for Reducing Pesticide Use, the government collected data from seed distributors on the active ingredients contained in the treated seed they imported and sold into the domestic and export markets. In contrast to farmer surveys, this does not allow linking the seed treatment information to particular areas of use and local environmental outcomes. The administration des services techniques de l'agriculture (ASTA) confirmed that seed is often imported from Germany, France, and Belgium, that many different combinations of active ingredients can be found on the seeds, and that standard seed treatments for imported seed can be quite different across these three countries. Since the EU banned the use of neonicotinoids, which are insecticides that are often applied as seed treatments, the seed treatments in Luxembourg contain mainly fungicides that protect the seed and the young plant from fungi.

A question of definition: What is considered a pesticide?

In other countries, pesticides applied as seed treatments have fallen through the cracks of government data collection efforts mainly because once the pesticide is coated onto a seed, the treated seed is no longer considered a pesticide. In the US, an EPA regulation (53 FR 15977) in 1988 exempted pesticide-treated articles, such as fungicide-treated paint, from the government’s definition of a pesticide and therefore also from pesticide registration and labelling requirements. Similarly, in the European Union, although the treatment of seeds with pesticides is considered a use of plant protection products, the sowing of treated seeds is not considered such a use (EC no. 1107/2009).

One ramification of this exclusion of seed treatments from the definition of pesticides concerns the export trade of treated seeds. Article 49 in regulation EC no. 1107/2009 allows treated seeds to be freely traded throughout the EU, such that it is permissible to plant treated seeds that were imported from other EU countries, even if the active ingredient contained in the treatment is not specifically registered for use in the country where the seed is planted.

Summary and outlook

Balancing the benefits and costs of pesticide use starts with accurate and complete data. As application methods have shifted from field spraying to seed coatings, data collection efforts have not kept pace, such that data on pesticide use are missing an increasingly important piece of the puzzle. And surveys that do ask farmers about the pesticides applied to their seeds produce less reliable data, because farmers are often unaware of the specific pesticide products applied to their seed. With its survey of seed distributors in 2019, Luxembourg is one of the first countries after the United Kingdom to systematically collect information on pesticides applied as seed treatments. For many other countries and for the EU overall, the lack of public data on pesticides applied as seed treatments makes the assessment of pesticide-related policies more difficult.

Author: Claudia Hitaj (LIST)

Editor: Michèle Weber (FNR)