Nobel Prize Assembly

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2020 was awarded jointly to Harvey J. Alter, Michael Houghton and Charles M. Rice "for the discovery of Hepatitis C virus.

This year’s Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine is awarded to three scientists who discovered that the majority of blood-borne liver inflammations (hepatitis) are caused by the Hepatitis C virus. Their seminal work made possible blood tests and new medicines that have saved millions of lives.

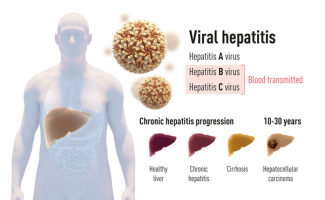

Figure 1. There are two main forms of hepatitis, which can form both acute and chronic liver inflammation. One form is an acute disease caused by Hepatitis A virus that is transmitted by contaminated water or food. The other form is caused by Hepatitis B virus or Hepatitis C virus (this year’s Nobel prize). This form of blood-borne hepatitis is often a chronic disease that may progress to cirrhosis and liver cancer (hepatocellular carcinoma) if not diagnosed early and treated adequately. (Illustration: The Nobel Assembly)

Prior to the three scientists’ work, the discovery of the Hepatitis A and B viruses had been critical steps forward, but the majority of blood-borne hepatitis cases remained unexplained. A vaccine is available against hepatitis A and B, but not yet against hepatitis C, which is considered to be the most dangerous form.

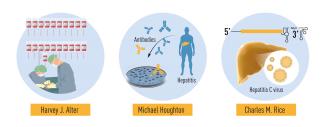

Figure 2. Summary of the discoveries awarded by this year’s Nobel prize. The methodical studies of transfusion-associated hepatitis by Harvey J. Alter demonstrated that an unknown virus was a common cause of chronic hepatitis. Michael Houghton used an untested strategy to isolate the genome of the new virus that was named Hepatitis C virus. Charles M. Rice provided the final evidence showing that Hepatitis C virus alone could cause hepatitis.(Illustration: The Nobel Assembly)

science.lu spoke to two scientists, who – either in the past or present – work(ed) on Hepatitis C in Luxembourg or in collaboration with Luxembourg. And one of them even did his doctoral thesis in the laboratory of Charles Rice, one of this year’s Nobel laureates.

What it is like to work in the lab of a Nobel Laureate

Thomas Dentzer, Charles Rice was one of the supervisors of your PhD thesis you did in collaboration with Luxembourg. You worked in his lab at Rockefeller University in New York between 2005 and 2011, including a post-doc. What do you think about this year’s Nobel Prize?

It’s a fantastic recognition for Charlie’s laboratory and all the work that has been conducted there in the past 15-20 years. For example, his lab was the first that could robustly grow virus in culture in the laboratory. That was a major breakthrough in Hepatitis C virus research, not least because it opened the door to drug development.

The Nobel price also reflects the atmosphere of the team that surrounded Charlie during these days. Most of them are now well-established researchers.

In what way?

Hepatitis C is nowadays a disease that can be cured, and there are hopes to eliminate the virus from the globe. When I started my PhD, maybe 20-25% of patients could be cured. Today it can be over 90%. And this is thanks to sensitive blood tests and effective anti-Hepatitis-C medication. Because to date, there is no vaccine against Hepatitis C.

What was your PhD thesis about?

The Hepatitis C virus is composed of 10 proteins. I worked mainly on one of those proteins to identify its function and potential points of attack for therapies that would prevent viral replication.

Did you actually meet Charles Rice in person? What is he like?

Oh yes, all the time! He is not one of those laboratory heads who you never actually see in the lab. His door was always open and if you worked hard and had interesting results, he was always keen to hear about it. The best time to catch him was Sunday morning though – I used to go for a run on Sunday mornings and then go to the lab to have a chat with him.

That sounds like dedication…from both of you!

Yes, Charlie is totally dedicated to science, he lives and breathes sciences. And he has an amazing drive to achieve things, to move things forward. When you work in his lab, you “inherit” some of this culture. Charlie is an inspiring person and the experience at Rockefeller University formed me in a great way. I learned that anything is possible and that you can have an impact on the world.

Are you still in touch with him?

Yes, I am. Charlie is not a big Socialite, but whenever I am in New York, I go and visit him. And I have to do two things: drink a Pepsi Max with him and bring him a bottle of Luxembourgish white wine. He loves his dogs and his wine collection – and he really likes Luxembourgish white wine!

Thomas now works at the Direction de la Santé at the Ministry of Health. He is playing an important role in the management of the current COVID-19 pandemic. Which, just like Hepatitis C, is also caused by a double-stranded RNA virus.

HCV testing and care in Luxembourg: two best practice’s examples in Europe

In Luxembourg, the prevalence of Hepatitis C is estimated to be 0.7% in the resident population. The majority of newly notified cases of Hepatitis C virus infection are people who inject drugs – likely due to unsafe drug injection practices. Nevertheless, there is no systematic approach to infectious diseases testing of persons accessing drug treatment services in Luxembourg and no formal system for active linkage to care. Drug use is also the most important risk factor for the infection in people in prisons.

Carole Devaux, Deputy Head of the Infectious Diseases Unit at the Luxembourg Institute of Health (LIH), is involved in pilot projects that introduced systematic Hepatitis C screening and care in harm reducation centres and a prison in Luxembourg. Both models help reduce the burden and transmission of Hepatitis C and were selected as best practice examples in Europe.

Carole Devaux, can you first tell us a bit more about the pilot project in harm reduction centres?

Between 2015-2019, we have conducted a pilot study, called HCV-UD, at the national drug consumption facility (Abrigado) and in 3 different drug substitution treatment sites (Kontakt 28, Jugend an Drogenhellef and AbriSud) to investigate the profiles and practices of people who actively inject drugs. We established an interventional programme to propose proactive screening and medical care to those people. From the 449 drug users who participated, 55 received a direct-acting antiviral treatment. In total, 67 were followed for their Hepatitis C virus infection.

We analyzed how common Hepatitis C virus infection was in this population each year and observed a decline in the percentage of Hepatitis C virus-infected persons in the population recruited at the drug treatment sites from 82 to 55 %. This decrease may be explained by the presence of the HCV-UD study at these sites since 2015 and by a real decrease in new HCV-infected people due to the increasing uptake of antiviral treatments. The study demonstrated the feasibility and acceptability of testing and care among drug users using harm reduction centers, including the proactive screening of this population.

And this success had an impact on multiple levels?

Yes, the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), which is reporting on a regular basis on drug-related infectious diseases in Europe, has selected innovative approaches from different countries for delivering Hepatitis C virus testing and care to people who inject drugs to present them as best practice cases. Among these is Luxembourg’s model of care HCV-UD.

Due to its success, the HCV-UD program has also been further expanded to organisations taking care of homeless people, medical offices of clinicians prescribing treatment substitution and in the other drug consumption room that opened end of July in Esch-sur-Alzette.

And last but not least, the programmes tested in the pilot are part of the national action plan against viral hepatitis.

What about the other project in prisons?

There is a high prevalence of viral hepatitis related to drug use in prisons. Therefore a standardized approach was implemented in 2009 to offer diagnosis, linkage to care, treatment and prevention measures in prisons, under a specialized medical department called COMATEP.

The work is done in collaboration with the National Service of Infectious Diseases. All inmates are systematically offered screening for different viral disease, including Hepatitis C virus, during a consultation with a doctor within 24 hours of arrival in prison. The acceptance rate of the screening protocol is very high (>95%). In the case of a positive test result, a consultation with an infectious diseases specialist is immediately organized in the prison clinic for the initiation of appropriate antiviral therapy, follow-up on viral load, immunization, and/or ultrasound tests. Antiviral treatment for hepatitis C is provided within the prison clinic when the duration of the treatment with the treatment fits with the period of incarceration. Nurses also organize counseling and make appointments with infectious disease specialists outside the prison and with NGOs upon the discharge of inmates.

Among the inmates that received and finished antiviral treatment for Hepatitis C virus infections, 96% achieved an undetectable viral load. That means their Hepatitis C virus infection can be considered cured.

The COMATEP program was selected by the World Health Organisation (WHO) in 2020 as a good practice example in a Compendium of good practices in the health sector response to viral hepatitis in the WHO European Region.

Last question: Do you think the Nobel Prize will have an impact on those programmes?

Luxembourg makes considerable efforts to reduce the disease burden among the most vulnerable population: drug users with unsafe drug injection practices. Drawing attention to Hepatitis C virus through the Nobel Prize is a great opportunity to raise awareness among the general public and help target particularly this vulnerable population in Luxembourg.

The national action plan against viral hepatitis is funded by the Ministry of Health of Luxembourg and managed by the Comité de surveillance du SIDA, des hépatites infectieuses et des maladies sexuellement transmissibles, of which Carole Devaux is the President (vice-president Dr Vic Arendt).

Link to the press release of the Nobel Prize Assembly

Interview: Michèle Weber (FNR)

Photos: Nobel Prize Assembly (main image); LIH (Carole Devaux); Thomas Dentzer

Infobox

The program is developed jointly by the Infectious Diseases Unit at LIH’s Department of Infection and Immunity (Dr Carole Devaux) and the National Service of Infectious Diseases of the Centre Hospitalier de Luxembourg (CHL, Dr Vic Arendt) with the support of research nurses of the Clinical and Epidemiological Investigation Center, Luxembourg Institute of Health (infirmière coordinatrice HCV-UD Mme Graziella Ambroset).