Joël Mossong is an epidemiologist at the Laboratoire nationale de santé (LNS) and an expert in modelling the spread of viruses.

No time? Short version at the end of the article!

Joël Mossong, you are an expert in modelling the spread of viruses. A very direct question right at the beginning: how long will this situation last here in Luxembourg?

That is difficult to say. It’s a new virus and there are new developments every day. We have to learn that we cannot make long-term plans and forecasts in the current situation and that we have to re-evaluate them from day to day, from week to week. At the same time it is important to inform people transparently and honestly. If I were now to give an estimate, despite all the uncertainties, I would say that this situation must be maintained in this way for at least another six to twelve weeks. It would not surprise me either if the schools were to remain closed until the summer holidays. That is certainly a possible and perhaps necessary scenario. But there could also be positive surprises - and then everything could go faster.

What would those positive surprises be?

For example, the rapid discovery of a vaccine. Usually, this takes time. I estimate three to six months would be realistic. But maybe a vaccine will be available earlier – that is however not very likely. Or researchers may discover that an already approved or new drug has a prophylactic effect, as it was the case with swine flu. For the flu, for example, the drug Tamiflu can be given as a preventive measure, which is particularly appropriate for older people in CIPAs and people with risk factors. This would particularly help to reduce the crowds in the clinics.

So many months of near standstill... The question arises whether it could not somehow get resolved faster? What if the virus could just be spread in an unlimited way?

Or a similar argument: According to some experts (and also according to the German Chancellor) about 70% of the population will be infected with the virus sooner or later. From then on, society would be sufficiently immunised and the virus would be under control. So why shouldn't the virus simply spread quickly so that we can get to this point faster - and the spook is over?

That would be catastrophic! You can quickly work it out. In that case, some 450 000 people would be infected in Luxembourg within a short space of time, three to six months. If one assumes a mortality rate of 1%, about 4,500 people would die of Covid-19 in this period. This is close to the number of people who normally die in Luxembourg over the course of one year. In addition, the health system could collapse - because one would have to expect a few thousand people who would need intensive medical care within a short period of time. Even though Luxembourg is currently working hard to organise more beds, breathing apparatuses etc: that would be just too many patients. A terrible scenario. Doctors would probably have to decide who to admit and who not to admit (which, by the way, is currently the case in Bergamo, Italy). The selection criterion is determined by who has the best chance of survival - that is, people with other complications or chronic diseases would risk not being able to be treated. But, very importantly: we are not yet on this path! Decision-makers and politicians in Luxembourg and Europe have reacted quickly and very far-reaching measures have been taken.

Do you think that Luxembourg has reacted well?

Yes, I think that our government and other key decision-makers reacted very quickly. And I am positively impressed with how well people are reacting to the situation. Surely there are still some who do not follow all restrictions. But many have understood the gravity of the situation and that everything depends on how we act now. It is impressive to see that we have built up a system here in an extremely short time that is almost as restrictive as the system in Wuhan. But there, people were forced to do so much more. A lot of things also work for us because of a high willingness to cooperate as a society. In any case, it is right and necessary that we all avoid physical contact as far as possible. This is the only way to reduce the rate of infection. The key thing is to keep the infection rate as low as possible so that the health systems do not collapse. This must be our top priority! And this can only be done when there is hardly any physical contact, otherwise too many people will simply become infected and it will get out of hand. Or, to put it in more scientific terms: ...we need to get the rate of dispersion of the virus below 1. On average, each infected person may infect less than one other person - then the spread decreases and the virus is under control. If the distribution rate is above 1, the number of newly infected people increases steadily and sooner or later the health system risks collapse.

Is it sufficient to keep the virus under control? Wouldn't it be better to try to kill it completely?

That's a theoretical possibility. But then you would need a much stricter restrictions than the current measures. We would have to close the borders and put Luxembourg under a near total quarantine for six to eight weeks (for which we would then lack the nursing staff). That would be the time it would take for the new infections to terminate in the households as well.

But Luxembourg is right in the middle of Europe. The virus could easily be carried back into the country and everything would start all over again.

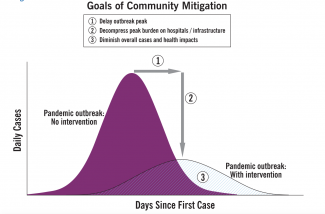

Exactly. Luxembourg cannot be considered in isolation. Nor do I think that option is realistic. I prefer what I call the "seeping fire scenario": In this scenario, we try to keep the number of new infections under control by using restrictive measures like avoiding physical contacts. We have to keep this number low so that not too many patients need intensive care and thus our health system does not collapse. This scenario is very similar to the principle "flatten the curve" (see infobox at the end of the article).

How long will this situation last?

Until drugs or vaccines are found and we can protect society. Or until a larger fraction of the population is infected and therefore immunized. But that would take a long time in this scenario...

What if we tried to get back to normal too soon?

Then we risk that after a short time the spectre would start all over again: the number of newly infected people would rise rapidly again and another shutdown would be necessary to avoid overburdening the health system.

So it is better to be patient and get everything right than to return to normality too quickly?

Exactly. I realise that the economic pressure is enormous, but all EU countries are in the same boat. But I have the impression that politicians and many people are aware that the social damage would be much greater if the opposite would happen.

Are the current measures sufficient to guarantee this "seeping fire scenario"?

This is an eminently important question! To be honest: we do not know yet. The effects of this restrictive measures will only become visible in 1 to 2 weeks. That is roughly the time after which the number of new infections in Wuhan no longer increased but decreased - and that also corresponds roughly to the time between a new infection and the appearance of symptoms or between a new infection and a positive test result. Unfortunately, we can only see the effects of the restrictive measures in the figures after a long delay. The measures introduced will certainly have a positive effect. Whether they are sufficient to push the distribution rate below 1 - this cannot be read in the data thus far. The data we are currently seeing have much more to do with access to and capacity for laboratory testing than with the real number of infected people in the population of Luxembourg.

So you are not shocked by the daily increase in the number of newly infected people?

No, that was to be expected. For two reasons: One, because we're simply doing testing more. Luxembourg's private labs have recently started helping out, there are drive-in stations. If we test more, there are automatically more people who have tested positive. So, at this stage, we must be extremely cautious in evaluating these data and not over-interpret them. In reality, there are probably more people infected than those diagnosed as positive cases. Secondly, we know that, initially, the number of newly infected people increases exponentially. This means we must also be prepared for the fact that there is an increase in the number of people who have symptoms, who go to the Maisons médicales or who need hospital treatment. In the next 1-2 weeks we should hopefully see the first positive effects of the Luxembourg measures.

It is of course difficult for politicians to make political decisions with such complicated data. Is there a lack of data? And yes, what could be done?

Surely it is a problem that at this stage the data cannot yet be trusted. On the other hand, politicians know - based on experience in other countries and with other epidemics - what has to be done. "Prepare for the worst, hope for the best" is precisely the pragmatic approach that Luxembourg has chosen. Work is in full swing to make more beds and ventilators available. This is right and important, even if we cannot at present estimate exactly how many people will ultimately have to go to intensive care or die. But better data is of course also important, because many other important political decisions will have to be made in the future - including whether restrictive measures needs to be strengthened or whether it can be relaxed after a while. A very important decision will also be when we reopen the schools and when we allow economic activity and physical contact again. It is important that we create a good database for these upcoming decisions as soon as possible. To this end, a national initiative is currently underway in which statisticians, researchers and officials are working together with the aim of providing better data and statistics for decision-makers. I myself, for example, have launched a survey via Twitter, which can also be found on science.lu as of today. We would be happy if as many people as possible took part. Our results so far: in a 2008 study, the Luxembourgers had direct physical contact with an average of 16 people every day, but the trend now seems to be towards fewer than five. We seem to be on the right track. However, we do not yet know whether this is enough.

The question is also how long will people stick to it?

That's right. The behaviour of each individual is crucial! The more disciplined and solidary we are, the sooner we can get the virus under control. And then it is important that in the current situation people's basic needs continue to be met: eating, drinking, sleeping, feeling safe and secure and communicating with our family, friends and work colleagues. As long as this works, I am confident that we can do it.

Overall, you seem relatively calm and positive about the situation. However, we are currently experiencing an exceptional situation the like of which we have never known before.

The measures that have just been taken were necessary. I have the impression that overall people have understood this. And it shows how versatile and creative people are. It is very impressive how people have completely changed their behaviour in a short period of time and also deal with it creatively. We talk a lot about "social distancing" at the moment - but I would prefer the term "physical distancing". Because, even if we have to avoid physical contact, I don't have the impression that people have less social contact. The contact only takes place in another form: via video conferencing, telephone and social media. The prerequisite for this is, of course, access to a well-functioning Internet.

We spoke earlier about normality. After everything you have said, it is hard to imagine that the same normality as we have known before will quickly return...

That's as clear as mud! The world will be a different place after this. At least for months to come. These events will certainly have a long-term influence on our travel and tourism behaviour. Also on our willingness to be controlled, such as taking our temperature. Nor will it be possible to open the borders overnight in the same way as before. We are also currently becoming aware of what professions are really essential to keep a society going in times of crisis: Nurses, supermarket cashiers, garbage collectors...

One last question: there are still people who claim that the coronavirus is not worse than the flu. What do you answer them?

I tell them: the flu is less contagious. The mortality rate is also lower by a factor of at least 10. In other words, the coronavirus is more deadly than the flu. The flu has been around for a long time. Many of us have had several flu infections in our lives and a larger part of the population is therefore immune. For this reason, the flu wave in winter lasts only 2-3 months. This is not yet the case with the new coronavirus. We as a society are currently at the mercy of the new coronavirus, if we do not take drastic action measures - as is currently the case. And finally: there is a vaccine for the flu. So there is another way to protect people. In the case of the novel coronavirus this is not (yet) the case. So: the coronavirus is clearly worse than the flu at the moment!

Joël Mossong, thank you very much for the interview!

Summary: The current restrictive measures are necessary. To do nothing would be catastrophic. But the politicians in Luxembourg have reacted well, says Joël Mossong. Whether the current measures are sufficient remains to be seen. Perhaps they need to become even stricter, or perhaps they can be relaxed. The important thing is not to cancel the restrictions too quickly, otherwise everything risks starting all over again. The scenario that the schools will not re-open at all this school year must at least be considered. But maybe a vaccine or prophylactic medication will be found quite soon, and everything will happen faster than expected.

About the person: Joël Mossong, Head of Epidemiology and Microbial Genomics at the Laboratoire national de santé (LNS, Staatslabo), Twitter: @joel_mossong

Joël Mossong graduated from high school in Diekirch and then went to England to study for a bachelor's degree in mathematics and then a master's degree in modelling the spread of viruses. In his doctoral thesis, he set up a model showing how many people need to be vaccinated against measles so that the entire society is virtually immune and the virus does not continue to spread (answer: 95%). Joel Mossong then worked at the CRP Santé and now since 2003 at the Luxembourg Laboratoire national de santé (LNS). At the moment he is also working on the novel coronavirus. The aim of the project: to sequence the virus in order to identify different mutations. For example, there are already genetic differences between the coronavirus in America and Europe. The more extensive and longer the different countries now close their borders, the greater the differences will become. In this way, it will be possible to identify later where people have been infected. But the project is still in its infancy. We will report about it on science.lu in due course.

Author: Jean-Paul Bertemes (FNR)

Editor: Michèle Weber (FNR)

Illustration: CDC

Infobox

Flattening the curve means that instead of a rapid exponential increase in the number of infected people over a short period of time, the same number of infected people is spread over a much longer period of time. Only in this way can healthcare systems treat the maximum number of patients requiring hospitalization and intensive care.